🔧 Chapter 5: The Solution Stack – What Goes Into a System

Up to now we’ve talked about why temperature control matters and where the risk lives. This chapter is about the machinery—physical and digital—that actually keeps that risk under control.

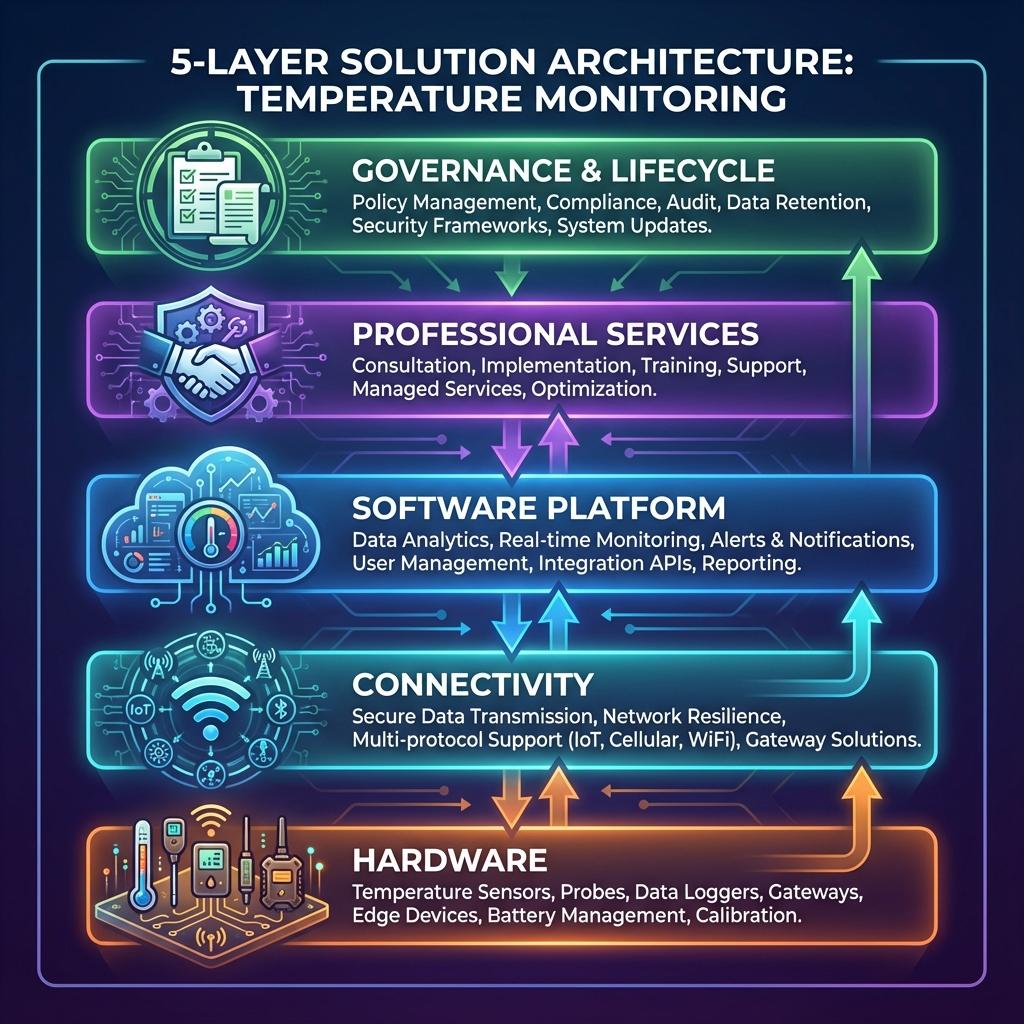

Think of it as a 4-layer stack sitting on top of a governance spine:

- Hardware

- Connectivity

- Software platform

- Services

- Governance & documentation (wraps all of the above)

If any layer is weak, the whole control system wobbles.

5.1 Hardware

The hardware layer turns the real world (air, product, equipment) into numbers you can trust. If you get this wrong, no amount of software or procedures will save you.

5.1.1 Sensor Types – RTDs, Thermistors, Thermocouples

There is no “best” sensor type; there is “fit for purpose”.

| Sensor Type | Typical Accuracy & Range (indicative) | Strengths | Limitations | Where It Fits Best |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTDs (e.g. Pt100) | High accuracy; roughly −200 to +200 °C | Very stable, repeatable, good for calibration-backed use | More expensive; usually need transmitters; wiring cost | Pharma warehouses, cold rooms, stability chambers, critical data rooms |

| Thermistors | High sensitivity in narrow range (e.g. −40 to +80 °C) | Excellent resolution around setpoint, compact, low-cost | Narrow useful range; non-linear; can drift | USB loggers, small cold rooms, transport loggers, retail cabinets |

| Thermocouples | Very wide range (up to 1 000 °C+ depending on type) | Rugged, cheap per probe, great for extreme temps | Lower accuracy, needs careful cold-junction compensation | High-temp mapping (autoclaves, ovens), some industrial processes |

For most mapping & monitoring of refrigerated / frozen / CRT spaces and data rooms:

- RTDs or high-quality thermistors are typically preferred where accuracy and traceability are critical.

- Thermocouples tend to appear for higher-temperature process validation or legacy systems.

Key selection questions:

- What temperature range do we need?

- What accuracy do regulations / internal standards demand?

- How often will we recalibrate and in what conditions (moisture, vibration, cleaning chemicals)?

5.1.2 Data Loggers & Probes

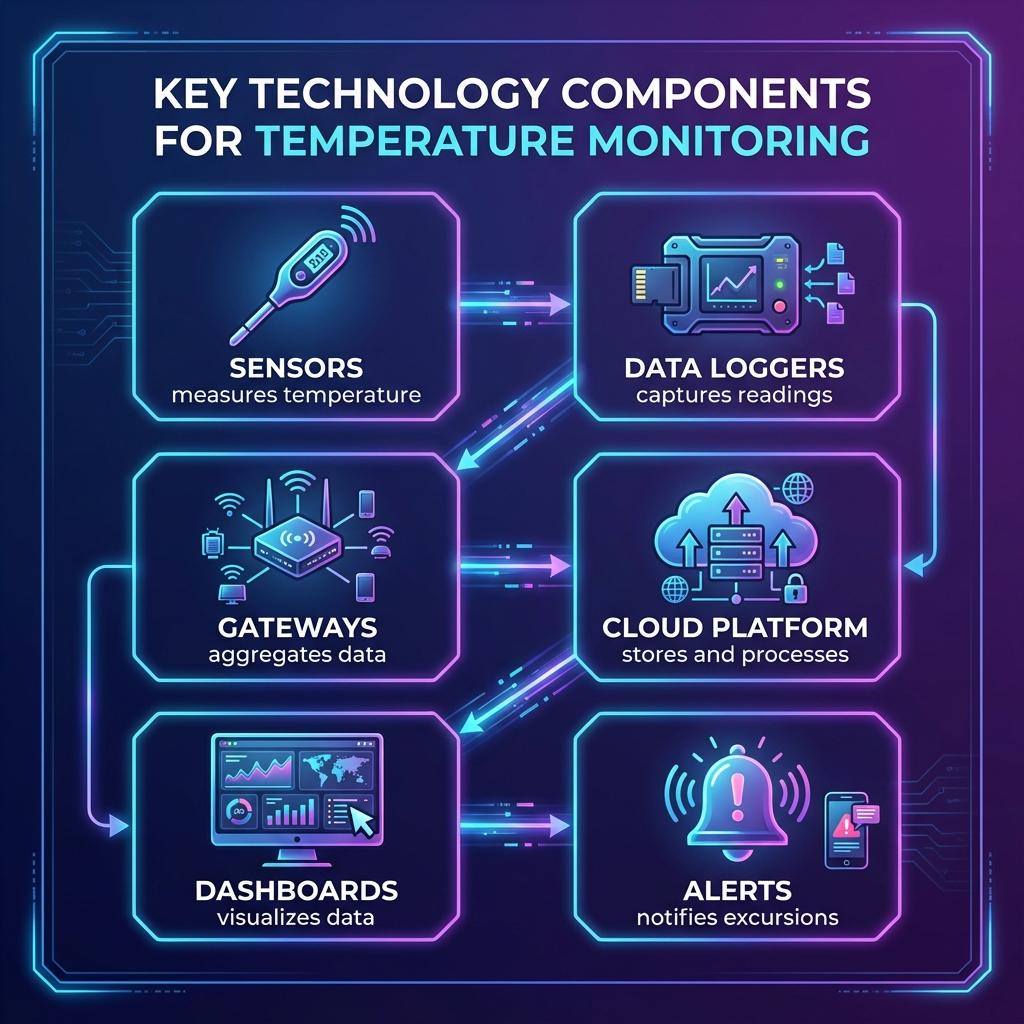

Sensors need a way to record and transmit their measurements. That’s where data loggers come in.

Common logger categories:

- Standalone USB / button loggers

- Small, battery-powered; often used in shipments or ad-hoc mapping.

- Data downloaded manually to a PC after a trip or study.

- Pros: cheap, simple, good for one-off mapping or lane qualification.

- Cons: manual handling, risk of lost devices / files, limited real-time visibility.

- Fixed loggers with local display

- Typically wall-mounted or panel-mounted with a small display (and sometimes min/max memory).

- Used in cold rooms, freezers, smaller stores.

- Pros: staff can see current conditions at a glance.

- Cons: if not networked, data are “local only”; still need manual downloading unless integrated.

- Networked loggers / transmitters

- Sensors wired or wirelessly connected to a central gateway / controller / server.

- Real-time or near-real-time data flow to a central platform.

- Pros: single pane of glass for multiple rooms/sites; easier alarm management; easier compliance.

- Cons: more complex infrastructure; needs IT/OT collaboration.

- Embedded probes in control systems

- Temperature sensors embedded in refrigeration controls, BMS, DCIM, etc.

- Often not originally designed as “GxP-grade” monitoring devices, so you must carefully assess accuracy, calibration, and data integrity before relying on them for compliance.

Battery life & memory

- For transport and remote sites, long battery life (months–years) and sufficient onboard memory to cover worst-case connectivity outages are critical.

- For fixed sites with mains power, the emphasis shifts to backup power (to ride out short outages) and robust internal memory or buffering.

5.1.3 Redundancy, Operating Ranges, IP Ratings

You’re not just selecting gadgets; you’re specifying survivability under real conditions.

- Redundancy

- Critical environments (e.g. high-value vaccine freezers, major data halls) often justify:

- Duplicate sensors in the same zone.

- Multiple independent data paths (e.g. logger + BMS).

- Redundancy planning should be risk-based: where is failure truly unacceptable?

- Critical environments (e.g. high-value vaccine freezers, major data halls) often justify:

- Operating ranges

- Ensure sensors and loggers are rated for the actual environment, not just the target product temperature.

- Example:

- Ambient around compressor heads or in rooftop locations may be much hotter than storage setpoints.

- Transport devices may see wide swings during handling.

- Ingress Protection (IP rating)

- Cold, wet, and wash-down environments demand appropriate IP ratings (e.g. IP65/IP67 for loggers in freezers or wash-down areas).

- In food plants, you may need devices that withstand cleaning chemicals and high-pressure wash.

5.1.4 Calibration & Traceability at Hardware Level

From a hardware standpoint, you should be looking for:

- Probes and loggers that can be physically calibrated (replaceable probes, calibration ports, etc.).

- Clear association between serial numbers and calibration certificates (no “mystery probes”).

- Support for labeling or tagging instruments with next-due dates and calibration status.

Your hardware shortlist should be filtered ruthlessly: if a vendor cannot clearly explain how each device is calibrated, how certificates are managed, and how traceability is maintained, they’re selling you a toy, not a measurement instrument.

5.2 Connectivity Layer

The connectivity layer is the nervous system: it moves data from the field to the platform. The challenge is to do that reliably, securely, and in a way that suits each environment.

5.2.1 Wired Options – RS-485, Ethernet, 4–20 mA

- RS-485 / Modbus / similar fieldbuses

- Workhorses in industrial and building environments.

- Pros: robust over long distances, good for multi-drop networks, widely supported.

- Cons: requires cabling and careful topology; not ideal for retrofits in finished spaces.

- Ethernet (TCP/IP)

- Common for gateways, some loggers, and BMS/DCIM integrations.

- Pros: high bandwidth, leverages existing IT infrastructure, easy integration via IP.

- Cons: Needs coordination with IT; careful network segmentation and cybersecurity controls in regulated sites.

- 4–20 mA / analog signals

- Still widely used in industrial controls.

- For compliance-grade monitoring, you must be sure the receiving system (PLC, BMS, recorder) is itself validated and that scaling and calibration are properly managed.

When wired makes sense

- New builds or major refurbishments where cabling can be installed neatly.

- High-EMI environments or locations where wireless is unreliable.

- Data centres and critical pharma areas where wired networks are already standard.

5.2.2 Wireless Options – LoRa, Wi-Fi, BLE, Cellular

Wireless gives you flexibility, but each technology has its own personality.

- Wi-Fi

- Good for offices, some warehouses and labs with existing infrastructure.

- Pros: easy to deploy if coverage is adequate.

- Cons: battery drain for small sensors; potential congested spectrum; may be subject to IT security restrictions.

- LoRa / LoRaWAN / Sub-GHz LPWAN

- Designed for low-power, long-range sensor networks.

- Pros: excellent penetration in warehouses and buildings, long battery life.

- Cons: lower bandwidth; often needs site-specific gateways; requires planning for message reliability.

- BLE / proprietary short-range

- Good for data loggers in smaller rooms or for “walk-by” collection.

- Pros: low power; simple for short distances.

- Cons: limited range; typically needs gateways or handheld devices for collection.

- Cellular (2G/4G/5G, NB-IoT, LTE-M)

- Ideal for in-transit monitoring where you don’t control local infrastructure.

- Pros: independent of local networks; global coverage (with roaming).

- Cons: recurring data costs; patchy coverage in some routes; need for offline buffering when signal drops.

Design considerations

- Battery life vs update frequency – faster reporting consumes more energy.

- RF propagation – metal racks, insulated panels, and machinery can shadow signals; site surveys are often necessary.

- Roaming & SIM management – for global fleets, you need a sane strategy for managing SIMs, data plans, and roaming rules.

5.2.3 Offline Buffering & Syncing

No network is perfect. Your architecture must assume temporary disconnections:

- Loggers should have enough onboard memory to store measurements during outages.

- Gateways should be able to buffer data and re-sync with the central platform once connectivity returns.

- The platform should clearly flag data gaps and provide tools to investigate them, rather than silently hiding missing periods.

For regulated environments, “the network was down” is not a good look. The system should degrade gracefully into store-and-forward rather than silence.

5.2.4 Network Segregation in Validated Environments

In pharma and other GxP contexts, you can’t just hang devices off the corporate Wi-Fi and hope for the best.

Typical patterns:

- OT networks (for operational technology – sensors, controllers) segregated from IT networks (business systems) via firewalls / DMZs.

- VLANs and access control lists to ensure only authorised systems can talk to monitoring devices and gateways.

- Formal change control for network configuration that affects validated systems.

- Clear documentation of IP ranges, firewall rules, and data paths as part of the validation package.

The point is simple: connectivity is not just an IT convenience; it is part of the validated state of control.

5.3 Software & Platform Capabilities

The platform turns raw measurement into decision-grade information. This is where compliance, usability, and scalability either shine… or collapse.

5.3.1 Real-Time Dashboards & Views

Good platforms give you:

- Environment views – room-by-room, cabinet-by-cabinet, rack-by-rack.

- Site views – a single site overview, highlighting areas in warning/alarm.

- Portfolio views – multiple sites, regions, and fleets on one map or dashboard.

- Trend charts – zoomable graphs for investigations, root cause analysis, and continuous improvement.

Look for:

- Clear indication of current status vs limits.

- Ability to overlay setpoints, alarm thresholds, and events (door opens, power outages) on trends.

- Time zone and daylight savings awareness when operating globally.

5.3.2 Alerting Engines & Escalation Logic

A platform without a serious alerting engine is just a fancy chart recorder.

Key features:

- Configurable alarm conditions

- High, high-high, low, low-low thresholds.

- Time-over-threshold logic to filter false positives.

- Interlocks with door sensors, defrost cycles, or maintenance modes where appropriate.

- Multi-channel notification

- Email, SMS, push notifications, on-screen alerts.

- Optional integration with on-call management tools or ticketing systems.

- Escalation rules

- If an alarm is not acknowledged or resolved within X minutes, escalate to higher levels.

- Support for different alarm policies by site, environment type, or product criticality.

- Auditability of alarms

- Who acknowledged what, when, and what action they recorded.

- Ability to link alarms to deviations/CAPAs in your QMS.

5.3.3 Compliance-Grade Data Management

For GxP and similar contexts, your platform must behave like a serious regulated system, not a consumer app:

- User and role management

- Unique credentials; no shared logins.

- Role-based permissions (view, configure, acknowledge alarms, administer).

- Audit trails

- Automatic logging of configuration changes, user actions, data edits, and logins.

- Readable reports for inspectors.

- Electronic signatures (where used)

- Clear association with user identity and meaning (review, approval, etc.).

- Linked to specific records.

- Time synchronisation

- System clocks and device clocks aligned to a trusted time source.

- Time zone handling that avoids ambiguous timestamps.

- Retention & backup

- Configurable retention policies that meet or exceed regulatory requirements.

- Proven backup and restore mechanisms, with documented testing.

Even outside GxP, these features are incredibly useful for governance, forensics, and internal assurance.

5.3.4 Reporting & Integration (BMS, ERP, WMS, QMS, DCIM)

No monitoring system should be an island.

Essential integrations:

- BMS / DCIM / SCADA – for building-level alarms and energy optimisation.

- ERP / WMS – to link temperature history to inventory and batch records.

- QMS / LIMS – to feed deviations, CAPAs, and lab data.

- Service/ticketing tools – to route alarms into work orders.

Technically, you should look for:

- Modern APIs (REST/JSON or equivalent).

- Standard export formats (CSV, PDF, XML, etc.) for regulatory submissions and ad-hoc analysis.

- Ability to automate recurring reports (e.g., monthly excursion summary, calibration status, audit pack).

5.3.5 On-Prem vs Cloud vs Hybrid

There’s no universal right answer—only trade-offs:

| Deployment Model | Pros | Cons | Typical Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-Prem | Maximum control; easier to isolate networks; sometimes preferred by conservative regulators/IT | Higher internal maintenance burden; scaling multi-site can be painful | Single-site operations; organisations with strong internal IT/OT |

| Cloud / SaaS | Easier multi-site rollout; always-on updates; central view from anywhere | Needs strong data protection, vendor due diligence, and validation approach; dependency on internet | Global cold chain, multi-country operations, distributed data centre portfolios |

| Hybrid | Local gateways / caches + central cloud platform | More complex architecture but often best of both | Most cross-site, cross-country enterprises who want resilience + global visibility |

Whichever route you choose, the monitoring platform is business-critical; treat it with the same seriousness you give to your ERP, MES, or DCIM.

5.4 Services Layer

You don’t just buy a system—you buy the expertise to make it work, prove it works, and keep it working.

5.4.1 Temperature Mapping Studies

A credible mapping service typically includes:

- Scoping & risk assessment

- Define which spaces require mapping, under what conditions, at what frequency.

- Align with regulatory guidance and your internal risk appetite.

- Protocol development

- Number and placement of loggers.

- Test duration, loading patterns, door-opening simulations, seasonal considerations.

- Acceptance criteria and statistical methods.

- Deployment & execution

- Installation of calibrated loggers.

- Controlled execution of tests; logging of events.

- Analysis & reporting

- Identification of hot/cold spots, recovery times, and pattern anomalies.

- Clear recommendations: probe locations, “do not use” zones, layout changes, process changes.

- Handover & training

- Walkthrough of results with Quality / Operations / Engineering.

- Updates to SOPs and monitoring design.

Your evaluation should focus less on “how many loggers?” and more on methodology, documentation quality, and practical recommendations.

5.4.2 Validation & Qualification (DQ/IQ/OQ/PQ)

A serious provider should be able to support:

- DQ (Design Qualification)

- Reviewing specifications against URS and regulations.

- Helping justify design choices.

- IQ (Installation Qualification)

- Verifying correct installation of sensors, loggers, gateways, servers.

- Documenting serials, firmware versions, network details.

- OQ (Operational Qualification)

- Testing system functions (data capture, alarms, reports, user permissions, failover).

- Simulating excursions and verifying alarm behaviour.

- PQ (Performance Qualification)

- Demonstrating stable real-world performance over time under routine operations.

- Often integrates mapping results, real alarms, and actual responses.

This is where many “cheap” solutions fall apart: they can’t provide a coherent validation package, leaving Quality to reverse-engineer proof from scraps.

5.4.3 Calibration Programmes & Logistics

Beyond single calibrations, you need a programme:

- Asset register

- Unique ID for every probe, logger, gateway that is GxP-relevant.

- Link to location, environment, and calibration history.

- Schedule & reminders

- Defined intervals by instrument type and risk class.

- Automated reminders and tracking of overdue items.

- Execution options

- On-site calibration (for fixed devices).

- Swap-out programmes for transport loggers and field devices.

- Clear process for handling out-of-tolerance “as-found” results.

- Documentation

- Standardised certificates.

- Change logs when devices move between locations.

A strong vendor or partner will help you design this programme, not just send a calibration tech once a year.

5.4.4 SOP Development, Training & Audit Readiness

You’re not done when the system is live. People need to know how to use it and what to do when it screams.

Key service elements:

- SOPs & work instructions

- Mapping SOPs, monitoring SOPs, alarm response SOPs, calibration SOPs, backup & restore procedures.

- Aligned with your QMS and written in language operators actually understand.

- Training

- Role-specific: operators, supervisors, QA, engineering, IT.

- Initial roll-out plus periodic refreshers and new-joiner modules.

- Audit preparation

- Pre-audit reviews of mapping reports, validation packs, calibration status, alarm history.

- “Mock inspections” to rehearse responses and ensure documentation is coherent.

A lot of inspection pain comes not from actual failures but from inability to tell a clear story. The services layer should fix that.

5.5 Governance & Documentation

Finally, the layer that ties everything together: who owns what, and what proof you can put on the table.

5.5.1 Core Governance Documents

At minimum, a mature organisation should maintain:

- Validation Master Plan (VMP) – Sets the overall strategy for qualifying and validating temperature-controlled environments and monitoring systems.

- URS (User Requirement Specifications) – For each system/environment class: what must the solution do and why.

- Risk assessments – Mapping where failure modes live and how controls mitigate them.

- Mapping protocols & reports – For each warehouse, cold room, vehicle class, cabinet, chamber, data hall.

- Monitoring & alarm SOPs – Including escalation charts and action timelines.

- Calibration policy & schedules – Including criteria for extending or shortening intervals.

- Change control records – For system upgrades, sensor relocations, network changes.

- Deviation & CAPA records – Linked to alarms and excursions.

All of these should be version-controlled, accessible, and cross-referenced.

5.5.2 Requalification Plans & Lifecycle Management

Governance is not a one-time event.

- Requalification triggers

- Time-based (e.g., every 1–3 years by risk).

- Event-based (e.g., major modifications, repeated deviations, equipment replacement).

- Lifecycle view

- From initial commissioning → steady-state operations → upgrades → decommissioning.

- Each phase defined in the VMP and supported by SOPs and checklists.

The best organisations treat temperature control systems like living assets, not “projects we finished”.

5.5.3 Audit Support Kits

A very practical concept: for each major environment type (e.g., “Main Pharma Warehouse”, “Vaccine Cold Rooms”, “Frozen Food DC”, “Primary Data Hall”), assemble a ready-made kit that includes:

- Site overview & environmental classification.

- Latest mapping reports and probe layout diagrams.

- Monitoring system description and validation summary.

- List of sensors and calibration status.

- Last 12–24 months of excursions and investigations.

- Key SOPs and a contact list of process/system owners.

When inspections or customer audits happen, you don’t scramble; you open the kit.

5.5.4 Roles & Ownership

Governance fails when “everyone” owns it. Define:

- System Owner – Accountable for day-to-day operation of the monitoring system.

- Process Owner (Quality) – Accountable for compliance, URS, and decision-making rules.

- IT/OT Owner – Accountable for infrastructure, security, and connectivity.

- Calibration & Metrology Lead – Accountable for measurement traceability.

- Steering Group – Cross-functional review body for major changes, budget, and risk decisions.

Once the roles are clear, the stack in this chapter stops being a set of nice diagrams and becomes a governed system that regulators, customers, and boards can trust.

Use Chapter 5 as your technical reference backbone: when you draft URS, talk to vendors, or design multi-site rollouts, sanity-check everything against these layers. If a proposal looks great on one layer but weak on another (e.g., stellar hardware, terrible governance), you already know where the risk will show up later.

Solution Stack Architecture

This flowchart shows how the solution layers interconnect: