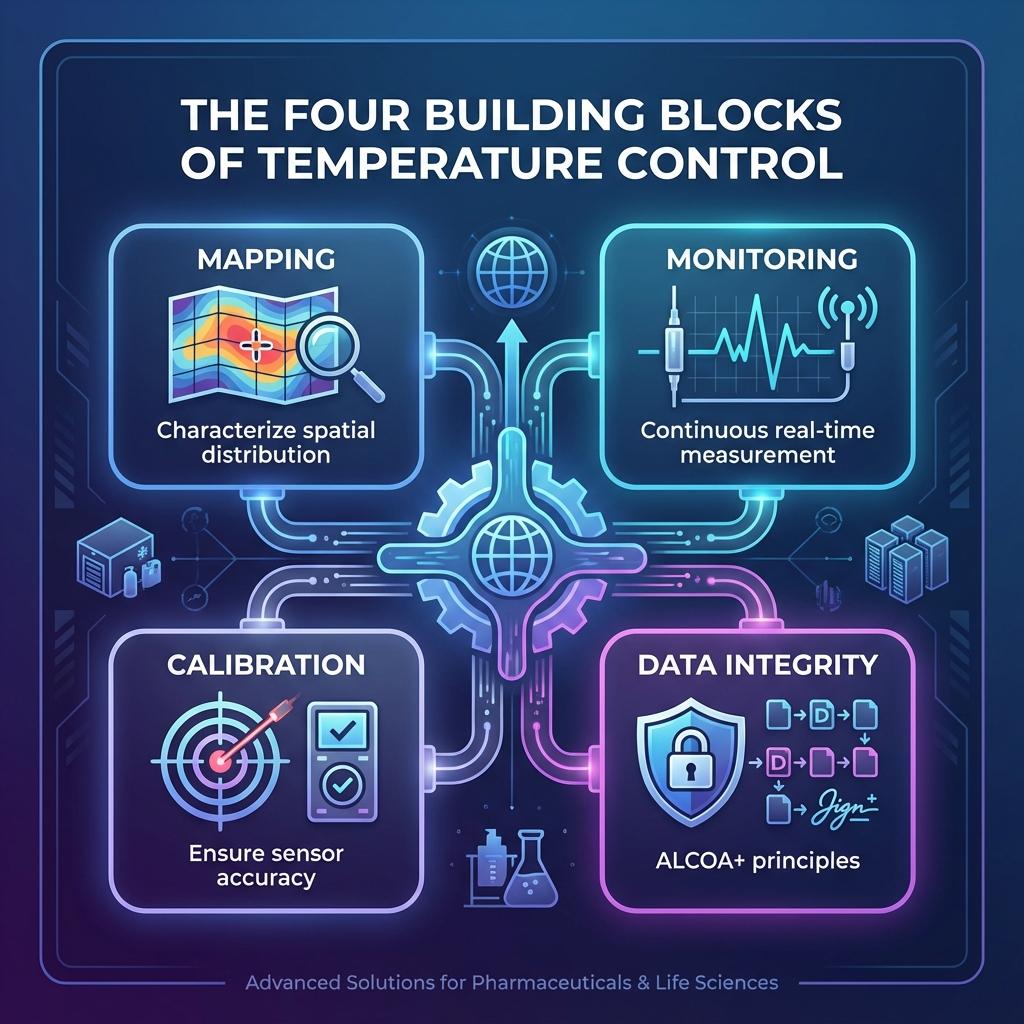

🧠 Chapter 2: Understanding the Building Blocks

This chapter creates a shared language. If everyone in the room—Quality, Operations, Engineering, IT, Procurement—is using “mapping”, “monitoring”, “calibration”, and “validation” interchangeably, you are one audit away from a very long day.

Here, we standardise the terminology and show how these elements fit together into a single lifecycle.

2.1 Glossary of Core Terms

These definitions are phrased for practical, buyer-side use—not as textbook theory. They are aligned with common regulatory usage (GMP/GDP, WHO guidance, ISO/IEC 17025, GAMP-style validation thinking).

2.1.1 Temperature Mapping

Temperature mapping is a structured study that uses multiple calibrated sensors to characterise how temperature (and sometimes humidity) is distributed in a controlled space over time.

Purpose

- Identify hot and cold spots, stratification, and unstable zones.

- Confirm that the entire usable volume stays within specified limits under realistic conditions (empty, partially loaded, fully loaded, seasonal extremes, door openings, etc.).

- Provide a factual basis for sensor placement, alarm limits, and loading patterns.

Typical outputs

- Mapping protocol (plan).

- Time-series data from many loggers.

- Statistical analysis (min/max, mean kinetic temperature, variance, excursions).

- Recommendations (e.g., “avoid top left corner for critical stock”, “add baffle”, “reposition evaporator fan”).

Mapping is an event or series of events—performed at initial qualification, after changes, and at defined intervals.

2.1.2 Temperature Monitoring

Temperature monitoring is the ongoing measurement, recording, and review of temperature (and sometimes humidity) at defined locations to confirm that a system remains in a state of control.

Purpose

- Detect deviations fast enough to act.

- Provide continuous evidence for audits, investigations, and releases.

- Support trend analysis (e.g., gradual equipment degradation, seasonal drift).

Key elements

- Properly located probes (based on mapping, not guesswork).

- Defined sampling and recording frequency.

- Alarm thresholds and escalation rules.

- Review and response procedures (who picks up the phone at 2:00 a.m. and what they do).

Monitoring is continuous or periodic by design; mapping is what makes that monitoring meaningful.

2.1.3 Calibration

Calibration is the documented comparison of a measuring instrument (e.g., temperature data logger, probe, RTD) against a reference standard with known accuracy, to quantify and (where appropriate) adjust its measurement error.

Purpose

- Demonstrate that sensors are accurate enough for their intended use.

- Ensure traceability to national / international standards (e.g., through ISO/IEC 17025-accredited labs).

- Establish correction factors or confirm that correction is not required.

Calibration is not:

- Just “checking that the display looks okay”.

- A one-time exercise at purchase.

It is a planned lifecycle activity with defined intervals, documentation, and decision rules (e.g., what to do if an instrument fails post-use).

2.1.4 Validation & Qualification

In regulated environments (pharma, biotech, many healthcare and high-risk settings), regulators expect you to demonstrate that your facilities, equipment, and systems are fit for their intended use and remain under control.

Two terms are frequently used:

- Qualification – Focused on equipment, utilities, and facilities.

- Validation – Broader, covering processes and systems (including computerised systems).

Within qualification, four well-known stages are often used:

DQ – Design Qualification

Design Qualification confirms and documents that the proposed design of the facility, system, or equipment is suitable for the intended purpose and aligned with regulatory and user requirements.

Typical content:

- URS (User Requirement Specification).

- Design specifications and drawings.

- Evidence that chosen equipment/control strategy can achieve required temperature ranges and stability.

IQ – Installation Qualification

Installation Qualification documents that the system has been installed correctly and according to approved specifications and manufacturer recommendations.

Typical content:

- Equipment identification and calibration status.

- Verification of installation details (location, connections, power, networking).

- Software installation records, user account setup.

OQ – Operational Qualification

Operational Qualification verifies and documents that the system operates as intended across specified operating ranges under controlled test conditions.

Typical content:

- Tests of setpoints, alarms, and failsafes.

- Verification that sensors read correctly over relevant temperature ranges.

- Simulation of excursions and alarm responses.

PQ – Performance Qualification

Performance Qualification demonstrates that the system performs effectively and reproducibly in routine, real-world operating conditions.

Typical content:

- Mapping runs under normal loading and usage patterns.

- Evidence of stable performance across realistic environmental/seasonal variation.

- Confirmation that monitoring + response processes work in practice.

Note: In many organisations, temperature mapping studies are a key component of OQ and/or PQ, depending on how protocols are structured.

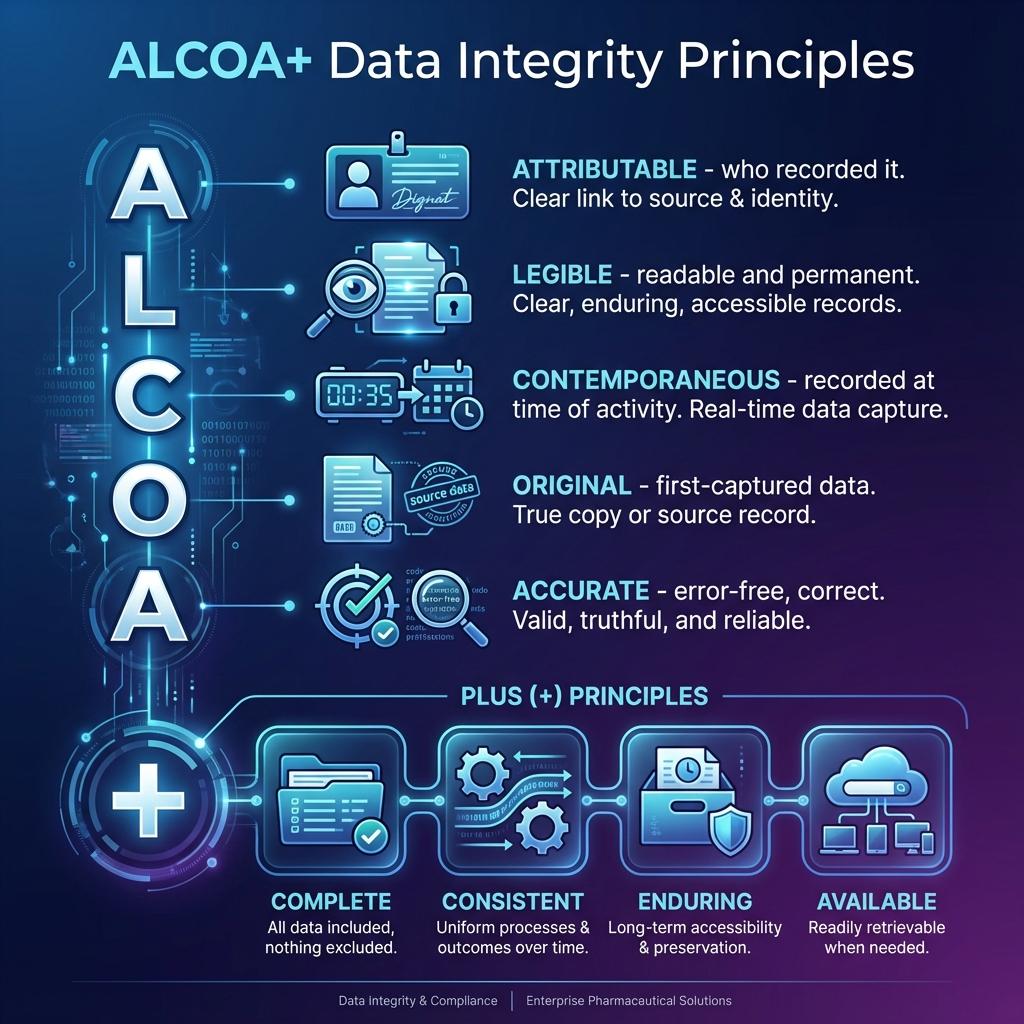

2.1.5 Data Integrity & ALCOA+

Regulators increasingly view data integrity as non-negotiable. It is not enough for temperatures to be “in range”; you must show that your data is reliable and trustworthy.

ALCOA stands for Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate.

ALCOA+ extends this to include commonly accepted additional attributes such as:

- Complete – All data (including repeats, aborted tests) is retained.

- Consistent – Time sequence is logical and unbroken.

- Enduring – Data is recorded on durable media and retained as long as required.

- Available – Data is accessible for review, audit, and investigation.

Applied to temperature mapping and monitoring, ALCOA+ implies:

- Every reading is linked to a specific instrument, location, time, and user or system process.

- Data cannot be altered without trace; any change must leave an auditable trail.

- Electronic records and signatures are secure, with appropriate access controls.

- Data is backed up, protected from loss, and retrievable in human-readable form.

In other words: if you can’t trust the data, you can’t trust the control.

2.2 Mapping vs Monitoring: The Lifecycle View

Mapping and monitoring are often treated as separate topics, sometimes even handled by different vendors. In reality, they are two phases of a single lifecycle of control.

2.2.1 When and Why Mapping Is Required

While exact expectations differ by regulator and industry, the following situations almost universally call for temperature mapping:

- New facilities or equipment before first use

- New warehouses, cold rooms, freezers, stability chambers, data rooms.

- New transport equipment (reefers, containers, vehicles) before being used for critical products.

- Significant modifications or changes

- Capacity upgrades, layout changes, racking modifications.

- Replacement of critical components (e.g., refrigeration units, control systems, CRAC units).

- Changes in loading patterns (e.g., switching from mixed-use to high-density, single-product storage).

- Periodic requalification

- To confirm environments remain within specification over time.

- To capture the impact of gradual drift (e.g., insulation ageing, equipment wear, changing ambient conditions).

- Frequency is typically risk-based, but often in the range of 1–3 years for critical storage (and sometimes more frequently for high-risk or high-value contexts).

- Investigations and special studies

- After a serious deviation or recurring near-misses.

- When failures suggest unknown hot/cold spots or unstable behaviour.

Mapping is essentially the “reality-check” phase:

Is the environment actually behaving the way the drawings and design assumptions said it would?

Without mapping, monitoring is at best partial and at worst misleading, because you don’t really know where the risk zones are.

2.2.2 How Mapping Informs Probe Placement, Risk Zones, and SOPs

A good mapping study doesn’t just produce colourful graphs; it re-wires how you design control.

From mapping to probe placement

- You identify extreme points (hottest, coldest, slowest to recover) and representative points (areas where most product resides).

- Monitoring probes are then located to:

- Capture worst-case behaviour for alarms.

- Represent typical stock conditions for routine review and release.

From mapping to risk zones

- You may define zones like:

- “Preferred storage zones” for highest-risk products.

- “Do not use” zones (e.g., extreme top racks, corners near doorways).

- Zones that require faster rotation or additional packaging controls.

From mapping to SOPs and work instructions

- Door opening practices (e.g., maximum time, use of air curtains).

- Loading patterns (e.g., not blocking evaporators, fans, or airflow paths).

- Defrost cycles and their timing (e.g., outside peak operational windows).

- Maintenance and inspection routines based on observed weaknesses.

In a mature system, once mapping is done:

- Probe placement diagrams become controlled documents.

- Alarm setpoints are justified by mapping data, not just “2 to 8 °C sounds good”.

- SOPs explicitly reference mapping findings where relevant.

2.2.3 Continuous Monitoring and Alarm Management

Once mapping has defined where and what to monitor, continuous monitoring is the operational backbone of control.

A robust monitoring regime typically includes:

- Appropriate sensor density and location

- Minimum number of points defined by risk, room size, configuration, and mapping results.

- Logical coverage of high risk zones, doors, corners, and centre volumes.

- Sampling and recording

- Sampling interval set to detect excursions with sufficient granularity (e.g., 1–15 minutes for many controlled environments; more frequent for highly critical or sensitive ones).

- Buffered storage so data is not lost during connectivity outages.

- Alarm strategy

- Defined alarm thresholds (e.g., high/high-high, low/low-low).

- Time delay logic (to avoid nuisance alarms from transient events that don’t affect product).

- Clear, documented actions for each type of alarm (who does what, and by when).

- Notification and escalation

- Multi-channel alerts (local indicators, SMS/email/push notifications, integration with BMS/DCIM/SCADA where relevant).

- Escalation paths if the first-line responder does not acknowledge or resolve the alarm.

- Review and trending

- Routine review of trends to spot slow drifts, seasonal effects, and early signs of equipment failure.

- Periodic management review of monitoring performance, alarm frequency, and response effectiveness.

Without alarm management, continuous monitoring degrades into continuous recording, which helps only in post-mortems. The goal is not just to know that something went wrong—but to know fast enough to prevent damage.

2.3 Calibration: Trust in Every Degree

A beautifully designed mapping study and a sophisticated monitoring system can still fail if the sensors themselves are lying to you. Calibration is what keeps your numbers honest.

2.3.1 Calibration Methods

At a high level, temperature instrument calibration can be grouped into:

- Single-point calibration / verification

- Checking the instrument at a single temperature point (e.g., an ice-point check near 0 °C).

- Useful as a quick verification, but rarely sufficient alone for regulated use.

- Multi-point calibration

- Comparing the instrument against a reference at multiple points across its operating range (e.g., −20, 0, +25, +40 °C).

- Produces a calibration curve and allows more reliable error estimates.

- Typically used for GxP and other critical applications.

- Adjustment vs “as-found” calibration

- As-found: instrument readings are compared to the reference and errors are documented; no adjustment is made.

- Adjustment: instrument is adjusted to minimise error, then re-checked and documented.

- Both “as found” and “as left” data are important. If “as found” data shows significant error, you must assess the impact on past measurements.

- Laboratory vs in-situ calibration

- Lab calibration (often at an ISO/IEC 17025-accredited lab) offers higher control and traceability.

- In-situ calibration may be used for fixed sensors that are hard to remove, often with portable reference standards.

- Choice is driven by risk, regulatory expectations, and practical constraints.

For serious regulatory contexts, multi-point, traceable calibration is usually the expectation, not an optional upgrade.

2.3.2 Calibration Frequency – Principles, Not Myths

Regulators and standards bodies rarely prescribe a single hard-coded interval (e.g., “every 12 months regardless of use”). Instead, they expect calibration intervals to be risk-based and justified, considering:

- Instrument type and quality.

- Historical stability (how often it drifts, and by how much).

- Criticality of the measurement (e.g., vaccine freezer vs non-GxP comfort monitoring).

- Environmental stresses (vibration, humidity, chemical exposure, thermal cycling).

However, common starting points in practice for critical temperature monitoring devices are often:

- Annual calibration for most GxP and critical cold chain loggers and probes.

- Shorter intervals (6 months or even quarterly) for highly critical points or instruments with known drift issues.

- Extended intervals only where there is robust historical data showing stability, and a documented justification.

In addition, good practice usually includes:

- Verification on receipt (before first use).

- Verification after repair or adjustment.

- Verifications in between full calibrations, especially for critical instruments (e.g., quick reference checks).

The key is not to memorise a magic number, but to document a calibration policy that is sensible, evidence-based, and applied consistently.

2.3.3 Internal vs Third-Party Calibration

You effectively have three options:

- External accredited lab calibration

- Calibration performed by a laboratory accredited to ISO/IEC 17025 (or equivalent) for the relevant parameters.

- Provides high-confidence traceability and is often the default expectation in regulated pharma/biotech contexts.

- Typically used for initial calibration and periodic re-calibration of critical instruments.

- Internal calibration with external traceability

- Your organisation maintains in-house calibration capabilities using reference standards that are themselves calibrated by accredited labs.

- Requires appropriate facilities, documented procedures, trained personnel, and internal quality controls.

- Can be highly effective for large fleets of instruments if properly managed.

- Simple internal verification only

- Non-critical contexts sometimes rely on simple internal checks (e.g., ice point checks, comparison to a reference thermometer).

- Acceptable only where justified based on risk and not in place of proper calibration where regulatory expectations are explicit.

For regulated environments, third-party accredited calibration or a properly managed internal system with accredited traceable references is usually required to withstand scrutiny.

2.3.4 Traceability and Calibration Certificate Interpretation

A calibration certificate is not a decorative PDF to be filed and forgotten. It is a technical document that should answer key questions about the instrument’s fitness for use.

A robust calibration certificate should include:

- Unique identification of the instrument (serial number, model).

- Identification of the calibration provider and their accreditation status where applicable.

- Description of the calibration method and environmental conditions.

- The reference standards used and their own traceability.

- Calibration results at each test point, including:

- Nominal temperature.

- Instrument reading.

- Error (difference between reading and reference).

- Measurement uncertainty.

- Whether any adjustment was made, and if so, “as found” and “as left” data.

- Signature or approval of the responsible person and the date of calibration.

From a buyer’s perspective, you should be able to use the certificate to answer:

- Does the instrument stay within our required accuracy limits at all relevant temperatures?

- If not, do we accept it with a correction factor, or is it rejected?

- Are we comfortable with the uncertainty of the measurement for our application?

- What is the impact on historical data if “as-found” readings were out of tolerance?

Finally, traceability means:

You can follow a documented chain from your instrument back to national/international standards, without gaps.

If that chain is weak, undocumented, or opaque, your entire temperature control story rests on an assumption, not evidence.

How to Use This Chapter

As you move into later chapters on regulatory drivers, environments, solution architecture, and URS/evaluation:

- Use this glossary to keep everyone aligned on what each term means.

- Use the lifecycle view to challenge solutions that treat mapping, monitoring, calibration, and validation as isolated tasks rather than a connected system.

- Use the calibration principles to pressure-test vendors: anyone who cannot speak clearly about calibration, traceability, and data integrity is not offering a serious solution—no matter how sleek their dashboards look.

ALCOA+ Data Integrity Flow

This flowchart shows how data flows through the ALCOA+ principles: